Working for god, not money

The day of silence gets awkward: navigating silent interactions within the empire. How to live in poverty yet flourish: group industry without private property. The economics of love: guaranteed employment for life.

Lunisolar moment: New moon. Sun slow (clock ahead of sun).

Note: This is the third post of the new season and new publishing schedule.

The day of silence gets awkward

Most wisdom traditions say that loving god and loving the world are at odds because they are different ways of life. If that’s true (and it is in my experience), then sooner or later it’s going to get awkward, or worse. Sure enough, my experimental way of loving god is starting to get awkward.

I spend Wednesday nights and Thursday mornings at my mother’s house. At 84 years old, she’s less active these days, and living alone, she can benefit from more company at home. My sister and I are helping her get some quotes for big purchases: home insurance, a new roof, a hurricane-strength garage door.

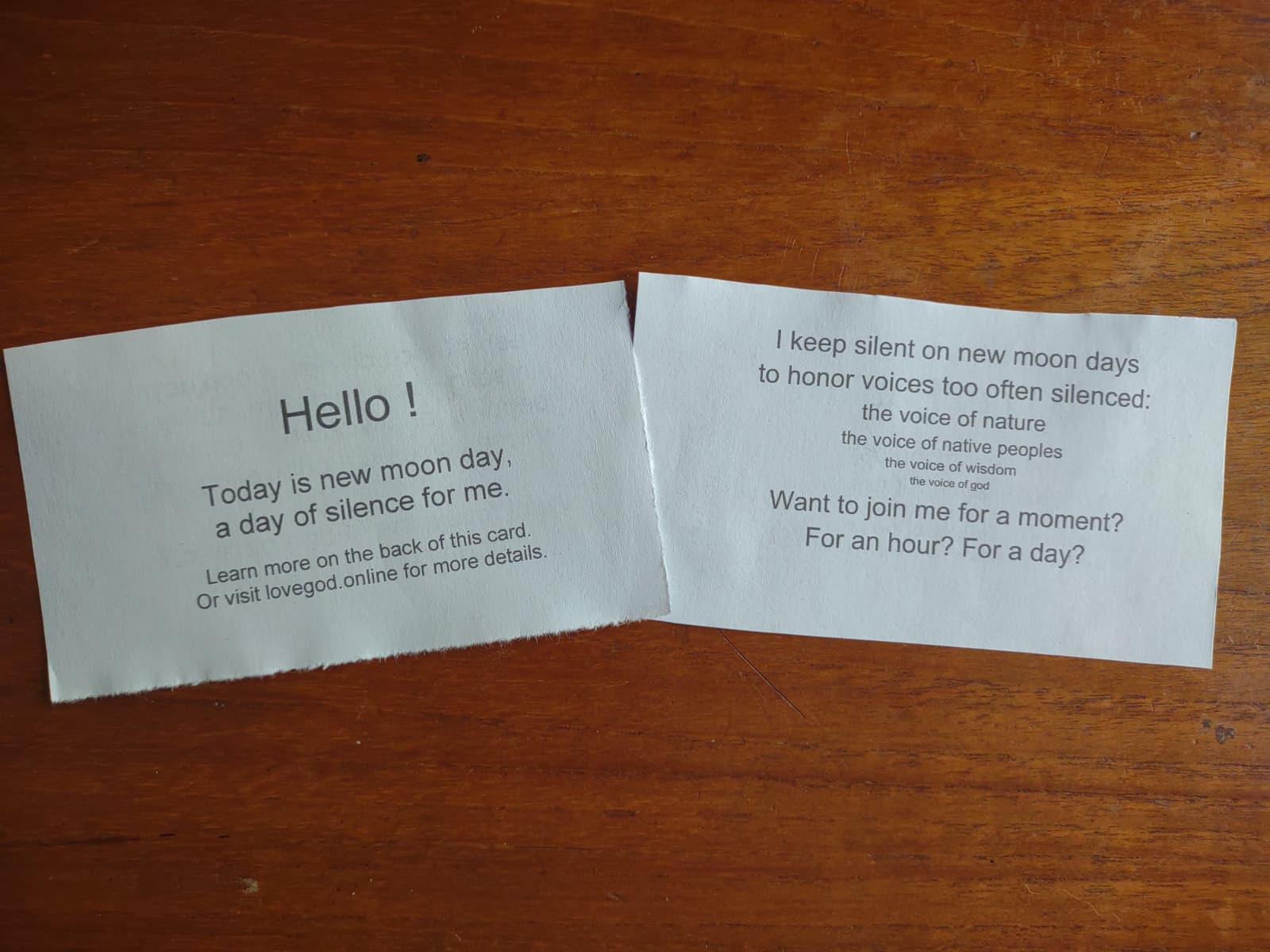

Last week, not realizing that Thursday, July 24, was new moon and a day of silence for me, I made an appointment with a garage-door company to get a quote July 24 between 9:00 and noon. The garage-door tech arrived on schedule, before noon.

I could have avoided the encounter. But when I weighed the alternatives in my mind for a moment, I thought, “Who am I to deprive this person of an alternative perspective? Maybe this is a message he needs to hear? At the very least, it’s a message I can deliver. And it’s not about me, not really. I shouldn’t avoid an interaction for fear of awkwardness or embarrassment. I am committed to a new-moon day of silence, and I am committed to helping my mom.” I resolved to participate in the encounter, bringing my day of silence into an interaction within the empire.

As I stepped out into the garage, the garage-door tech said hello. I waved, but said nothing. I approached the front of the garage, where he was. He said something, maybe “How are you?” I handed him a rough draft of my new-moon business card.

The garage-door tech read the card, front and back. Not knowing quite what to make of it, and perhaps not wanting to offend a potential customer, he nodded and said, “OK, that’s interesting. I never heard of that.”

From there, my mom did most of the talking. Using a notepad and pencil, I interjected with a few comments and questions here and there. We decided to hire them for the job.

Before he left, the garage-door tech asked if there was a website for my day of silence. I pointed out the url on the business card. He said he would check it out.

Never a dull day loving god. At the very least, it makes most days an adventure.

Rich in poverty

Last week we started looking at alternatives to capitalism. Both included vows of poverty. How does a community committed to poverty make a living? Simple. They renounce private property as individuals. They embrace industry as a group.

Religious communities have done this for centuries. Think of nuns running schools, hospitals, and other public-service ministries. Imagine friars tending grapes and making jam, growing hops and brewing beer, keeping bees and collecting honey.

These things are still happening, but ministries are not pursuing speed and scale. As a result, the corporate-empire model has prevailed, relegating the products and services of religious communities to the status of quaint relics. We, as willing consumers caught in craving and coveting, have fueled this move.

The Bruderhof and Plum Village are two exceptions worth analyzing. (Surely there are others, if you know of some, please share.)

The economics of love

In the case of the Bruderhof, two businesses provide a livelihood for most of the 3,000 adults and children who live in ~25 Bruderhof communities worldwide. Community Playthings has been manufacturing wooden toys and school furniture since 1947. In the 1980s, they added a line of therapeutic equipment for children with disabilities, now a separate business called Rifton Equipment.

These businesses fund Bruderhof schools, outreach, and publishing, including Plough, a literary journal. They also make it possible for the Bruderhof to do humanitarian work. Notice that they don’t call it philanthropy. They are not sitting on a pile of money. Their humanitarian efforts include meeting local needs, responding to disasters, and contributing money or labor to organizations such as Samaritan’s Purse and Save the Children.

In 2019, an editor of Plough quarterly interviewed Bruderhof brother John Rhodes, a manager of Community Playthings. The exchange (titled “Is Christian Business an Oxymoron?”) highlights unique elements and key energies underlying Bruderhof businesses. Due to space limitations, I’ll just share a few main concepts here.

“... But what’s really unusual about these businesses is that while they sell into the marketplace, internally they’re run communally. There are no bosses or employees, and everyone gets the same pay: nothing. We see our work as our contribution to a life in which we share everything as the first Christians did.”

“Is this socialism?” asks the editor. The Community Playthings worker replies:

Some might call it that, but I don’t believe in state control of the economy. The right question is, “What would the economics of love look like?” We try to live in such a way that our life answers that question.

Guaranteed employment: no hiring, no firing

Capitalism thrives on hierarchy. The extreme version is slavery. The lite version is dependency on wages. If a Bruderhof business has neither bosses nor wages, how does that work?

“Then there’s the question of bosses. Even in a fast-food restaurant, if you have a management position, you may not earn much more than the people flipping burgers, but you can at least boss them around. That’s something not really present with us.”

Capitalism also runs on ego, linked to private property. But take away the ego and private property through communal vows, and capitalism doesn’t work anymore.

Jesus says that the people of this world lord it over each other, but it should not be that way among us. If you walk into our workshop you will not very easily be able to tell who’s in charge. Yes, the work has to get done, but we’re in that together. If the person who was asked to be responsible for the shop were authoritarian or uncaring, we would find him another job. And that’s how we do our work everywhere in the community; things aren’t different just because this is the income-earning portion of our work.

Their work is rooted in communal life, and their common life is not rooted in money.

Finally, capitalism depends on profit, not relationships. Commonwealth runs on communal commitments to each other, for life.

If the community decides that my operations manager is needed for mission work abroad, he goes and I have to figure it out. And I can’t go out and hire anybody else. By the same token, I can’t fire anyone either. If there’s a problem, a change of assignment may be necessary, but we’re still committed to living and working together. So if there’s anything between us personally, we have to work it out.

Guaranteed employment in a higher purpose, for life.

Conclusion

For anyone seeking freedom from capitalism and shared commitments to holistic well-being, Bruderhof businesses are strong examples. May we create more like them.

Comments ()