Would Jesus celebrate Christmas?

Christmas in January? Remembering Jesus of Nazareth. Is religion private and personal or public and communal? “If you had control of the churches in a country, on what aims would you concentrate their forces?”

Cosmos: Full moon. Sun slow (clock ahead of sun).

In December and January every year, some 2 billion Christians celebrate Christmas in one way or another. Getting that many people to agree about anything is challenging. So we should not be surprised that there are multiple dates for celebrating Christmas:

- December 24 Scandinavian and Latin American countries

- December 25 Western Christianity and part of the Eastern churches

- January 6 Armenian Apostolic Church and the Armenian Evangelical Church

- January 7 Most Oriental Orthodox and part of the Eastern Orthodox churches

- January 19 Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem

We’ve talked before about time and calendars, so let’s leave those alone for now. For Christmastide – the time between Christmas (December 25) and Epiphany (January 6) – let’s talk about the prime inspiration for Christianity: our friend and teacher, Jesus of Nazareth.

To answer the title question, Would Jesus celebrate Christmas?, we can start by asking a related question: Did Jesus celebrate Christmas? As far as we can tell, Jesus did not celebrate Christmas. That does not mean we should not celebrate it, though this truth was enough for Puritans, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and many other Christian groups to abstain from Christmas, citing it as “unbiblical.”

What would Jesus do about poverty?

The first part of this question (rediscovered in the 1990s) comes from Charles Sheldon, a proponent of the Social Gospel, and his novel In His Steps: What would Jesus do? (1896). According to one historian, the Social Gospel (circa 1870-1920) was “American Protestantism’s response to the challenge of modern industrial society,” and its many social ills: namely child labor, poor schools, slums, economic inequality, poverty, alcoholism, crime, sex work, racial discrimination, and pollution.

It wasn’t just Protestants. Catholic Social Teaching arose around the same time as the Social Gospel and had many of the same goals.

Should a church help eliminate child labor? Should a congregation eradicate slums? Should churchgoers help improve poor schools? Social Gospelers said yes.

Today should a church help eliminate drug addiction? Poverty? Wealth inequality? AI “companions”? Nuclear weapons? Fossil fuels? Racism? Narcissism?

What are churches for?

A leading theologian of the Social Gospel, Walter Rauschenbusch (1861-1918) would appreciate these questions. His first book, Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907), inspired Martin King decades later in his use of the gospel to heal racism.

In 1918, Rauschenbusch posed the key question in The Social Principles of Jesus, his last book.

If you had full control of the churches in a given country or village community, on what aims would you concentrate their forces? (147-148)

Let’s imagine that for a moment. Where I live, in Palm Beach County, there are hundreds of churches. According to the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), in 2020 there were 908 congregations with 588,508 adherents across all religions. That is a lot of people, over one-third of the total population in a county with ~1.5 million souls at the time. The biggest single group is the Catholic Church, with 35 congregations and 285,977 adherents.

Further imagine if we could invite all those people to reform themselves and their way of life in way that was possible but also effective for overcoming a particular injustice. What would it be?

The short answer is money

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the spiritual wing of the civil rights movement, decided the answer was wealth inequality. After sparking incredible gains in federal legislation through nonviolent campaigns, they turned their attention to economics and wealth distribution. However, their last major effort, the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968, inspired only minor reforms.

The campaign was ultimately ineffective, yes, but it was a bold attempt to follow the teachings of Jesus. Many of his parables involve money (16 of 38), likely because (1) people understand money, AND (2) because money is a very dangerous resource. “Jesus exerted all his energies to bring men close together in love,” wrote Rauschenbusch. But“wealth divides,” creating “semi-human relations between social classes.” (121)

Medieval Christianity took seriously the principle that “private property is a danger to the soul and a neutralizer of love,” Rauschenbusch observed. However, the modern Christian world “has quietly set aside the ideas of Jesus on this subject [of private property], lives its life without much influence from them, and contents itself with emphasizing other aspects.” (125)

The fundamental tool of oppression

It should be no surprise, then, that Rauschenbusch saw an opportunity in this area. Here is Walter Rauschenbusch’s fuller response to his own question:

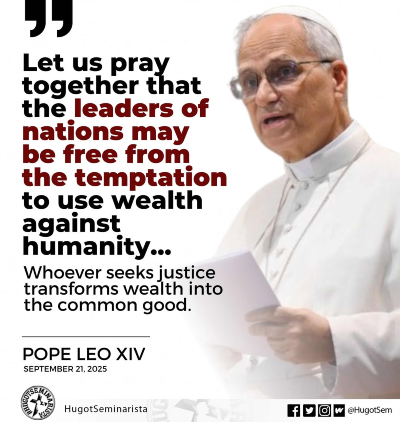

We need a Christian ethics of property, more perhaps than anything else. The wrongs connected with wealth are the most vulnerable point of our civilization. Unless we can make that crooked place straight, all our charities and religion are involved in hypocrisy.

He wasn’t saying all wealth was bad. Rather, the way we use wealth is bad.

We have to harmonize the two facts, that wealth is good and necessary, and that wealth is a danger to its possessor and to society. ... property is used as the fundamental tool of oppression.

Like Jesus, Rauschenbusch called out the noxious effect of accumulating wealth.

What is the relation between property and self-development? At what point does property become excessive? At what point does food become excessive and poisonous? At what point does fertilizer begin to kill a plant? Would any real social values be lost if incomes averaged [$100,000] and none exceeded [$1,000,000]? (127)

Today, how many Christian pastors call attention to wealth inequality on a regular basis? How many are actively involved in neutralizing the dangers of wealth? There are many, to be sure, but how many do you know? How many have you heard of?

Let’s answer those questions next time, god willing, to continue exploring the social side of religion, something that Jesus of Nazareth championed and modeled.

Repeating the healing parts of history

For now, let us take solace. We say history repeats itself. If that’s true (and I believe it is), then not only are the harmful parts of history repeated, but the healing parts of history are also repeated. If social-spiritual movements and economic revolutions have been sparked by Jesus and later followers over the centuries, surely they can be sparked by us as well. Let us continue to study, learn, and embody the teachings our society so desperately needs today.

Comments ()