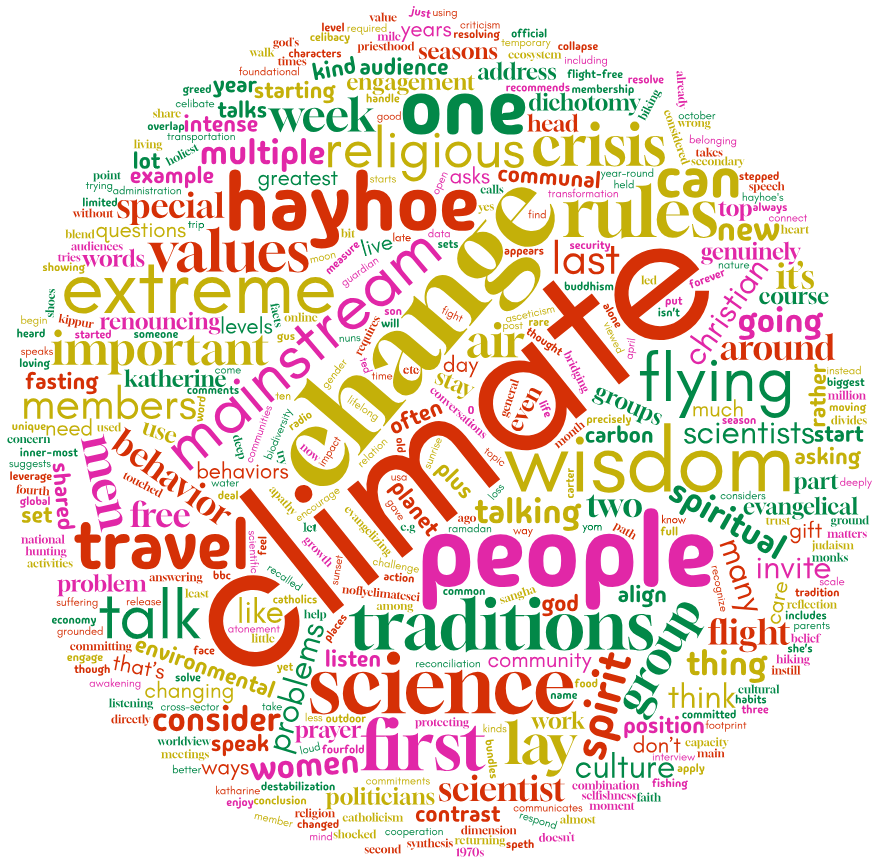

changing our words to change the climate

Wisdom traditions have different rules for different kinds of members. Universal rules apply to all members. Changing behavior around air travel may not be for everybody. Talking about climate crisis should be.

Protecting the climate starts with talking about it

Last week, on the new moon of April, I committed to a change in my way of life: renouncing air travel.

In the first post about this topic, I started answering common questions:

- How does this align with wisdom traditions?

- Why now?

- How will this help, if at all?

- Isn’t this a bit extreme?

I touched on the first three last week. Let me address the fourth one first this week.

Mainstream vs extreme: resolving the dichotomy

Yes, in our mainstream culture, going flight-free is extreme. Wisdom traditions almost always invite and encourage behavior that appears to be extreme to the mainstream culture. That’s why wisdom communities are often contrast people: groups living in contrast to the mainstream. Wisdom traditions handle this dichotomy in two ways.

- Most wisdom traditions have two sets of rules, at least: one for the “religious” members, and one for “lay” people.

- In Buddhism, there is a fourfold sangha: Religious men (monks), religious women (nuns), laymen, laywomen. Each group has its own set of rules.

- In Catholicism, priesthood is limited to men and requires celibacy. Lay Catholics are not required to be celibate.

- Religious members take the “extreme” path; laypeople are part of the mainstream in many ways.

- During special seasons of more intense engagement, wisdom traditions invite all members to more “extreme” behaviors – for a time.

- Ramadan, for example, is a month of fasting, communal prayer, reflection, and community, including no food or water between sunrise and sunset.

- Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year in Judaism, calls for “full fasting and asceticism,” communal prayer and atonement (reconciliation with god for release from suffering.)

- These behaviors are considered extreme by the mainstream. But because they are temporary, they are seen as less extreme than lifelong or year-round religious commitments.

How does this apply to behavior around air travel? Any wisdom tradition (new or old) that considers rules around flying/not flying could have multiple rules for different levels of membership: e.g., flight-free forever, no flying for 1 year, no flying during a special season, etc. But all members could agree on one thing: to care about the climate crisis in thought, word, and deed.

Science vs spirit

Returning to the other questions, how does renouncing air travel align with wisdom traditions?

First, it’s important to recognize the spiritual dimension of the challenge we face in climate destabilization in general, which includes the kinds of transportation we use and don’t use. Many people think of climate crisis as a problem for politicians or scientists to solve.

One of the first politicians to work on the problem in an official capacity, starting in the late 1970s during the Carter Administration, was Gus Speth. Looking back on those days, he sees his mistake.

“I used to think the top global environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change. I thought that with 30 years of good science we could address these problems. But I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed, and apathy, and to deal with these we need a spiritual and cultural transformation, and we scientists don't know how to do that.” Shared Planet: Religion and Nature, BBC Radio 4 (1 October 2013)

Spirit plus science

Katherine Hayhoe is a climate scientist. But like most people of faith, her position is secondary to her god. She is a Christian climate scientist, better yet, an evangelical climate scientist. That is a rare combination in our culture, but this kind of synthesis of spirit plus science is precisely the kind of cross-sector cooperation we need to resolve the climate crisis.

In an interview with The Guardian in 2021, Hayhoe recalled the moment of her awakening to the impact of her travel.

“Ten years ago I stepped on the carbon scale, so to speak, to measure my carbon footprint. I was genuinely shocked to find out that the biggest part of it was my travel. I was going to a lot of scientific meetings and going places to talk to people about climate change.” ~Katharine Hayhoe

She changed her habits, moving most of her talks online, flying much less.

She’s not alone, of course. Many scientists and lay people are changing their behavior around flying. For example:

But Hayhoe’s blend of spirit and science put her in a unique position to speak to people who have not heard someone like her care about climate crisis out loud, with loving speech and deep listening. Her work bridging divides led Hayhoe to this conclusion: “The most important thing you can do to fight climate change: talk about it.”

That’s the name of TED Talk she gave in 2018 that’s been viewed 4 million times. Her main point is not to talk about science. Rather, Hayhoe recommends, talk about values.

The most important thing to do is, instead of starting up with your head, with all the data and facts in our head, to start from the heart, to start by talking about why it matters to us, to begin with genuinely shared values. Are we both parents? Do we live in the same community? Do we enjoy the same outdoor activities: hiking, biking, fishing, even hunting? Do we care about the economy or national security?

With Christian audiences, she doesn’t try to change their values. Instead, she leverages values they already share. Speaking to Christian groups, Hayhoe asks: “What is God’s greatest gift to us is?” They respond: “His son.” But then she asks what god’s second greatest gift is.

“What if it’s this planet we live on?” she suggests to the audience. By first showing she’s a member of the same group and they have the same foundational worldview, audience members feel they can trust her, and they can listen to her with an open mind.

Individual change is great, says Hayhoe, but talking about climate can create more impact.

“Say that I put solar panels on my house. That’s great. But what if my place of work transitions to clean energy? You can calculate the difference, we’re talking orders of magnitude. But my place of work is only going to transition to solar energy if someone starts the conversation.”

Talking about climate change = a change in climate

I am not asking you to go flight-free, though I think you should consider it on some level. Like Katherine Hayhoe, I am asking you to talk about the climate crisis. Consider using that word – crisis – in relation to climate. Consider committing to conversations about climate – or even just comments about climate. Once a week? Once a day? What can you do? Change your words, change the climate.

Comments ()