good war: women

Black History Month. The centrality of black women to the Montgomery bus boycott. It would not have happened without them. Women made the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s by starting that good war. Women will remake the next civil rights movement in the 2020s.

Cosmos: Full moon. Sun slow (clock ahead of sun).

It’s February, Black History Month in the United States. This post focuses on the centrality of black women to the Montgomery bus boycott.

This is also the second post in a series of short essays on good war. In this short essay (4-minute read), we continue analyzing how the civil rights movement developed and operated in order to understand how we could do something similar today. Before picking up where we left off, a few words about good war.

A better way to resolve disputes

A good war is necessary whenever the forces of delusion, hatred, and greed become concentrated in unjust systems embedded in everyday life. This has been the case at many times in the United States, including in the 1950s in the south and in the 2020s everywhere.

In the 1950s the system had a name. It was called Jim Crow, and it was a series of state and local laws that made racism part of the legal framework of the southern US. Today the system is called capitalism. It’s an economic system built on a series of mental models that make greed part of everyday life in almost every sector of society.

Of course many other systems and models supported the main unjust system then and also now, including white supremacy, patriarchy, and casteism. But people waging war have limited resources and cannot afford to have too many targets. In a good war, overcoming even one unjust system is a major victory.

Nation states and military leaders engage in violent wars to resolve disputes they are unwilling or unable to resolve through peaceful means. Peacemakers and lovers of god wage nonviolent wars to resolve disputes they are unwilling to endure any longer.

Sacrificing self for a cause

In Waging a Good War: a Military History of the Civil Rights Movement 1954-1968, Thomas Ricks cites Richard Gregg, author of The Power of Nonviolence, for his insight into the connection between good war and destructive war.

Gregg endorsed the analogy between nonviolent actions and combat operations because he thought that many of the same behaviors and techniques that humans had developed over thousands of years to wage war could be repurposed for nonviolence. (42)

“The nonviolent resister,” Gregg wrote, needs “courage, self-respect, patience, endurance, and the ability to sacrifice himself for a cause,” just like soldiers in a violent war. War and peace, as it turns out, have much in common.

Filling in the details

In the first post in this series, we looked at five innovations coalesced in Montgomery as part of the year-long bus boycott in that city from December 1955 to December 1956. These innovations made winning a good war possible in our country in the 1950s and 60s.

Taking a deep dive into this list of strategies, here it is with major tactics and insights supporting the new group of organizers who were indispensable to the emergence of strategy #1: women.

- Women, labor, and church organizers collaborated on freedom campaigns, with churches leading the effort, catalyzing mass participation and maintaining it.

Women

- Rosa Parks, with no prior planning but with 12 years of experience struggling against segregation through the local NAACP, touched off a year-long boycott with her spontaneous noncooperation against the segregated seating system.

- Parks had been mentored by Septima Clark and others at Highlander Folk School that summer. The workshops she attended were about school integration but Clark encouraged her to find ways to desegregate her city.

- Virgina Durr, a white women who lived in Montgomery, paid for Rosa Parks to attend the training that summer.

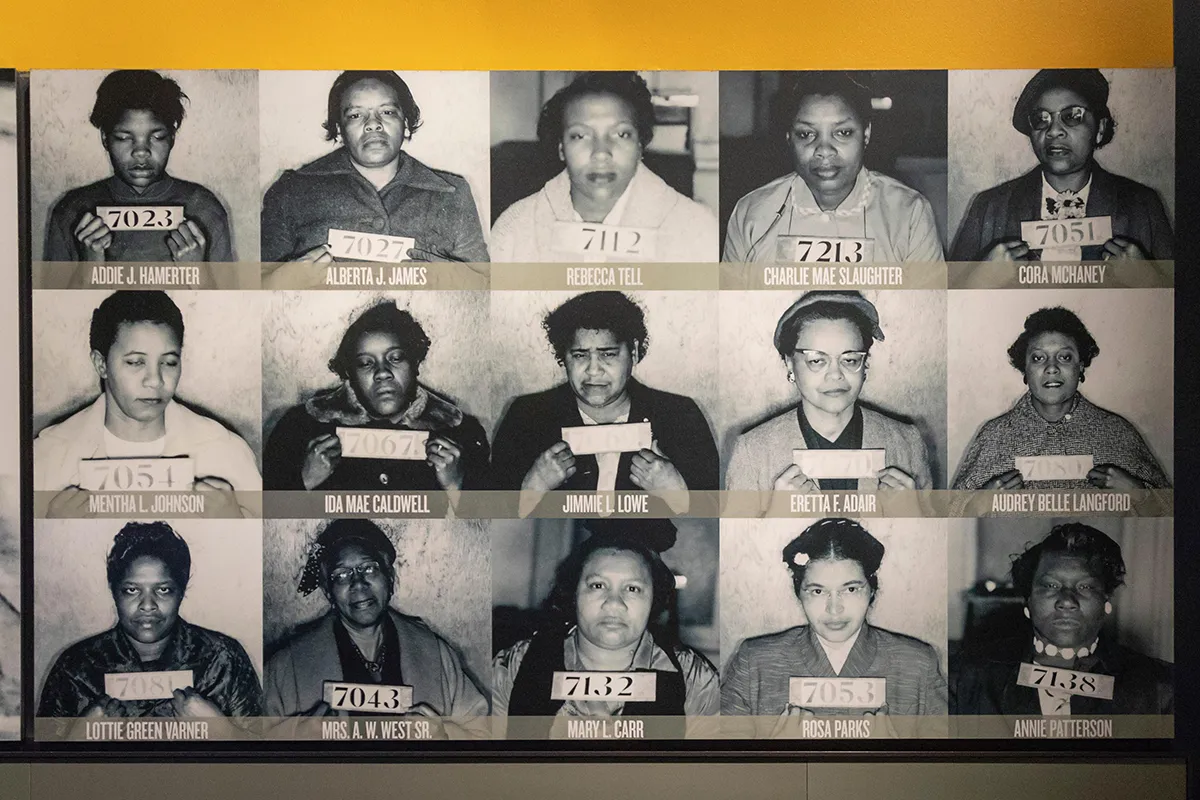

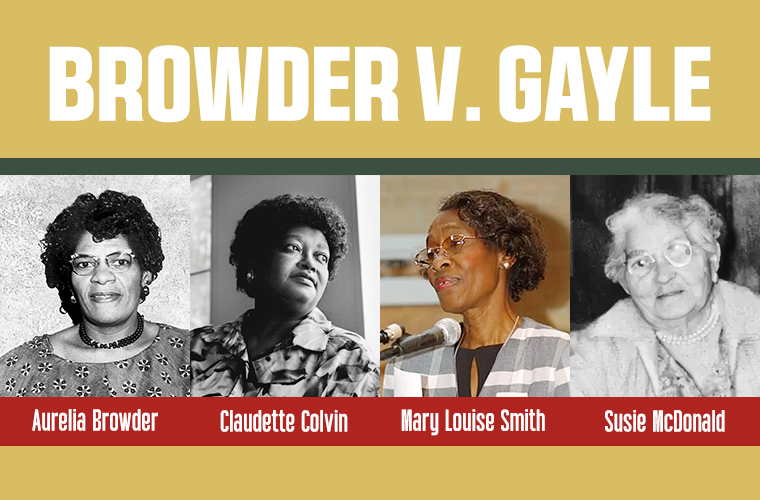

- Four women had been arrested in 1955 for doing exactly what Rosa Parks had done in December of that year: refusing to give up their seat to accommodate a white passenger.

- They were Claudette Colvin (arrested 3/2/1955); Auriela Browder (4/19/1955); Mary Louise Smith (10/21/1955); and Susie McDonald (10/21/1955).

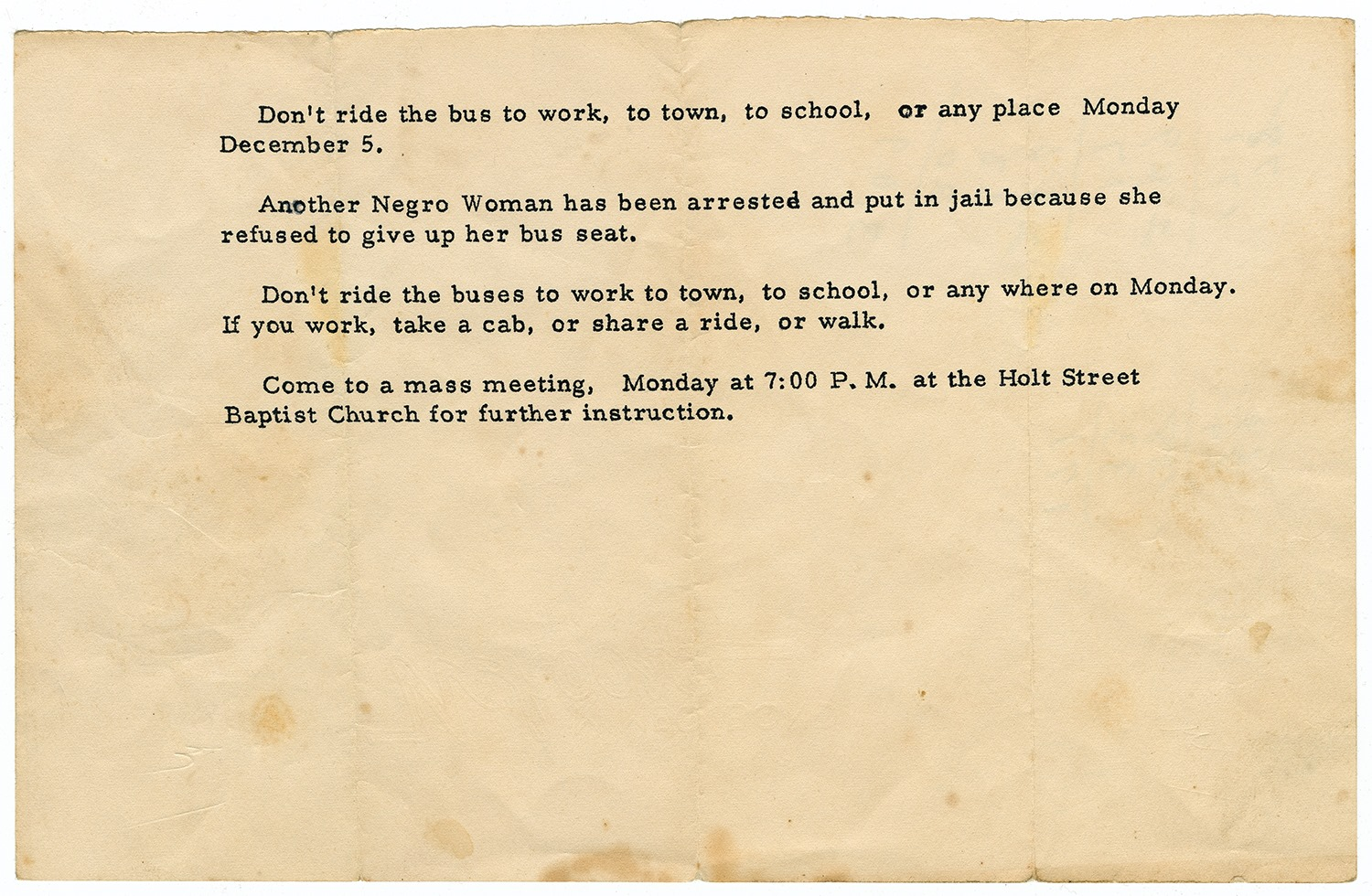

- The Women’s Political Council (WPC) of Montgomery called for the boycott after Parks’ arrest.

- Jo Ann Robinson, president of the WPC and professor of English at Alabama State College, “printed 52,500 fliers announcing the boycott. The three city divisions of the WPC, and students from the college, handed out the leaflets, covering the entire black community within a few hours. The leaflet told of Mrs. Parks’ arrest and urged blacks to stay off the buses on 5 December. Further, it announced a mass meeting for the entire community that evening to discuss the boycott and its goals.” (Val Heyer)

For context, here are the other strategies that emerged in Montgomery:

- Structured soul-force, aka nonviolent resistance, was applied en masse to overcome legal racism.

- Mass economic pressure was applied to segregated systems over weeks and months.

- The message of a love-ethic for justice was fully articulated and embodied.

- Television news brought the drama of nonviolent struggle into people’s living rooms.

Can there be any doubt that women started the Montgomery bus boycott? Can there be any doubt that women will be indispensable to waging a good war in our day?

Women made the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s by starting that good war. Men and customs held them back along the way. Women will remake the next civil rights movement in the 2020s. Nobody will be able to hold them back now.

Comments ()