good war: church

Black History Month continues. How the black church got involved in good war. Injustice is a spiritual problem. The most effective method for overcoming injustice is a spiritual solution.

Cosmos: New moon. Sun slow (clock ahead of sun).

This is the third post in a series of short essays on good war.

Peter Onuf, a historian of US history, claims that the civil rights movement was really America’s “good war” and the people who waged it were truly “greatest generation.” (Waging a Good War: a Military History of the Civil Rights Movement 1954-1968, xvi)

As a lover of god, I agree with this perspective. A false narrative of spiritual warfare often depicts it as dealing solely with invisible forces and praying for exorcism, for example. True spiritual warfare is challenging unjust systems through social prayer. The civil rights movement was spiritual warfare.

A spiritual problem

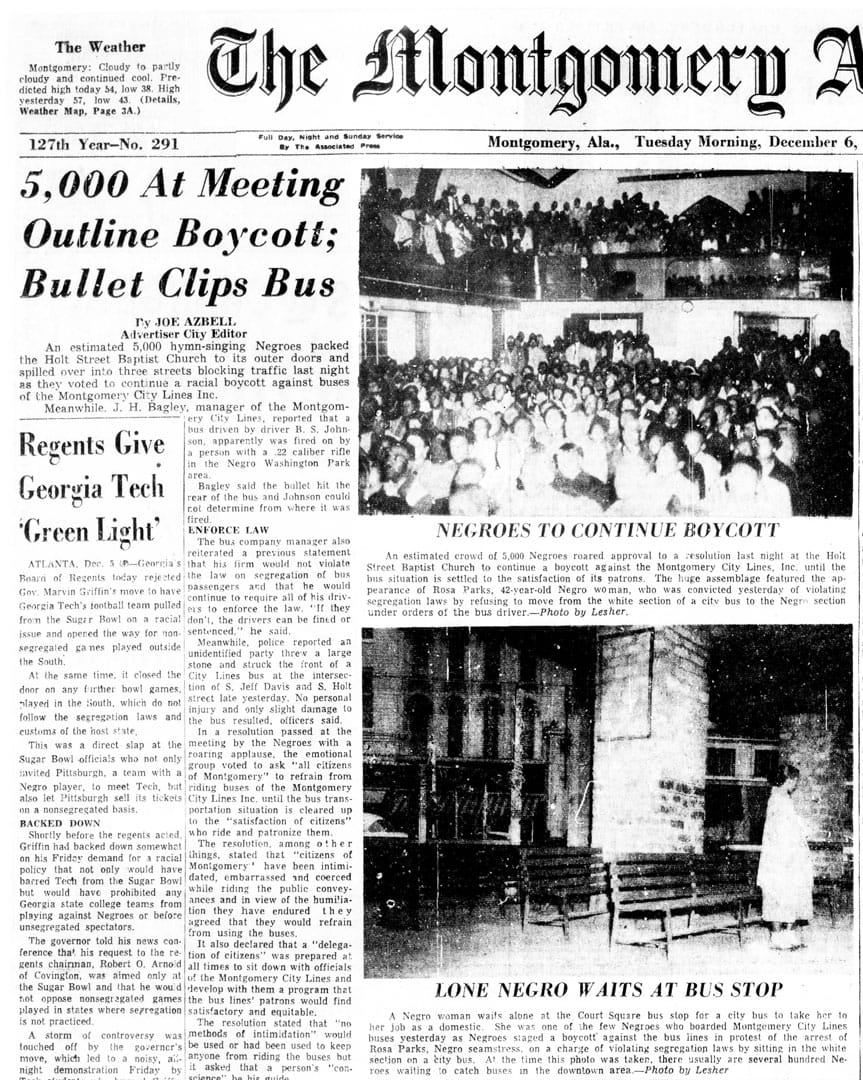

Shorty after a favorable US Supreme Court decision ended the Montgomery bus boycott, leaders of the movement articulated their struggle this way.

We call upon white Southern Christians to realize that the treatment of Negroes is a basic spiritual problem. We believe that no legal approach can fully redeem or reconcile man. We urge them in Christ’s name to join the struggle for justice. (“A Statement to the South and Nation”)

The movement itself was not strictly Christian. But the spiritual wing of the movement grew out of the black churches that, to everyone’s surprise, were at the forefront of the bus boycott. More about that surprise in a minute.

First, we need to learn from the spiritual wing of the movement at least two lessons:

- Injustice is a spiritual problem.

- The most effective method for overcoming injustice is a spiritual solution.

That’s the theoretical level of the work. I call it spiritual justice.

On the practical level, we need to apply the lessons of these spiritual innovators to our situation. The military historian, Thomas Ricks, put it this way.

“If we are to hold on to their gains and reinforce them, we must recognize the nature of their effort so that we can prepare ourselves to safeguard and sustain our democracy. From the movement, we may be able to abstract principles and approaches that we need in order to apply them to our situation now.” (Waging a Good War, xvi)

How the church went to war

Before the Montgomery bus boycott, the black church had mostly stayed out of integration efforts. W.E.B. Du Bois, a co-founder of the NAACP, “raised holy hell by denouncing black church leadership as inadequate to the task” of ending racial injustice, calling out preachers whose “sermons were out of date and provided no leadership.” (Richard Kluger, Simple Justice, 100) That was around 1910-1934.

Some 30 years later ...

In military terms, the churches had become the command posts of the movement, secure locations where plans could be made, training sessions held, and orders issued. … The southern black church was effectively a citadel for the movement. (Waging Good War, 32)

So what happened? How did the black church suddenly embrace good war, after decades of mostly avoiding it?

Not all black churches supported civil rights

To be sure, many black churches stayed out of the civil rights movement. In fact, there was a split in the black church in 1961 over that very issue. Martin King and other peacemaking preachers were on the losing side of the split that year. They were ousted from the National Baptist Convention, the largest black-church association in the country, because of their support for civil rights.

In Montgomery, the local pastors were pushed into a leadership role by women.

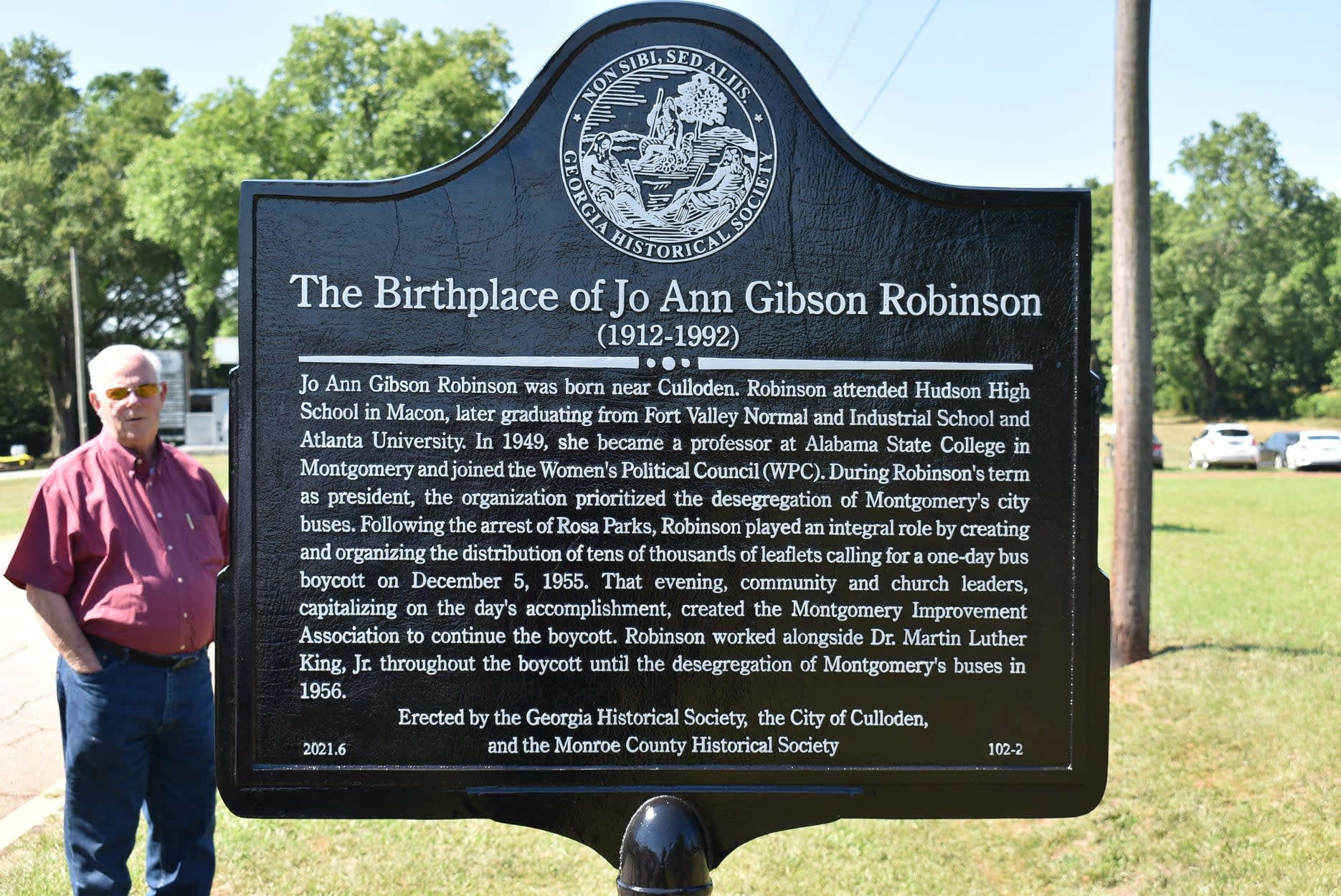

Jo Ann Robinson, the leader of the local Women’s Political Council, had notified the ministers of the upcoming boycott, but she had done so anonymously.

On Friday morning, December 2, 1955, a goodly number of Montgomery’s black clergymen happened to be meeting … It was easy for my two students and me to leave a handful of our circulars at the church, and those disciples of God could not truthfully have told where the notices came from ...

The ministers held their meeting and then discussed the news of the boycott.

One minister read the circular, inquired about the announcements [to stay off the buses], and found that all the city’s black congregations were quite intelligent on the matter and were planning to support the one-day boycott with or without their ministers’ leadership. It was then that the ministers decided that it was time for them, the leaders, to catch up with the masses. (The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson)

Today, if we as lovers of god and would-be peacemakers are not involving churches, we should be. The struggle to overcome the harmful elements of capitalism cannot be won without the church entering the war on our side.

Comments ()