good war: intro

The Montgomery action was the first spiritual campaign of the civil rights movement. That’s what made it revolutionary. It was the beginning of a good war that surprised almost everyone. And it’s exactly what we need now.

Cosmos: New moon. Sun slow (clock ahead of sun).

A year after the Montgomery bus boycott, Martin Luther King admitted how uninvolved he was in the genesis of this revolutionary event.

When I went to Montgomery as a pastor, I had not the slightest idea that I would later become involved in a crisis in which nonviolent resistance would be applicable. I neither started the protest nor suggested it. I simply responded to the call of the people for a spokesman.

The Montgomery action was the first spiritual campaign of the civil rights movement. That’s what made it revolutionary. It was the beginning of a good war that surprised almost everyone. And it’s exactly what we need now.

Lovers of god in Montgomery channeled innovations in peacemaking starting in December 1955. In the process, they developed a method that proved decisive in the struggle for civil rights over the next decade.

Today, if lovers of god want to spark and win future movements for peace and justice in the USA, we should study these innovations, and we should commit to this method. Let us begin that process with this short introduction to good war.

Innovations of the Montgomery campaign

There were several firsts in the Montgomery bus boycott, innovations that would become vital to the movement.

- It was the first time women, labor, and church organizers collaborated on a unified campaign in the south, with churches leading the effort, catalyzing and maintaining mass participation.

- It was the first time soul-force, aka nonviolent resistance, was being applied en masse to overcome legal racism.

- It was the first time mass economic pressure was leveraged over many months in the south.

- It was the first time the message of a love-ethic for justice was fully articulated as part of the movement.

- It was the first time television news was covering an extended campaign in the south.

To unpack part of innovation #1, take a look at the entities involved by category:

- Women: the Women’s Political Council and the Montgomery Improvement Association (four paid staff, all women)

- Labor: Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Union

- Civil rights groups: the local NAACP and Voters League

- Churches: The local Methodist Ministerial Alliance, Baptist Ministers’ Conference, and Inter-Denominational Ministerial Alliance

The other part of innovation #1 is perhaps the more important one: churches were leading the way. This meant that the message of the movement would be different. Now it involved god.

The underlying message of the boycott was something like this:

If you love god, and if you love your country, you have to support this bus boycott.

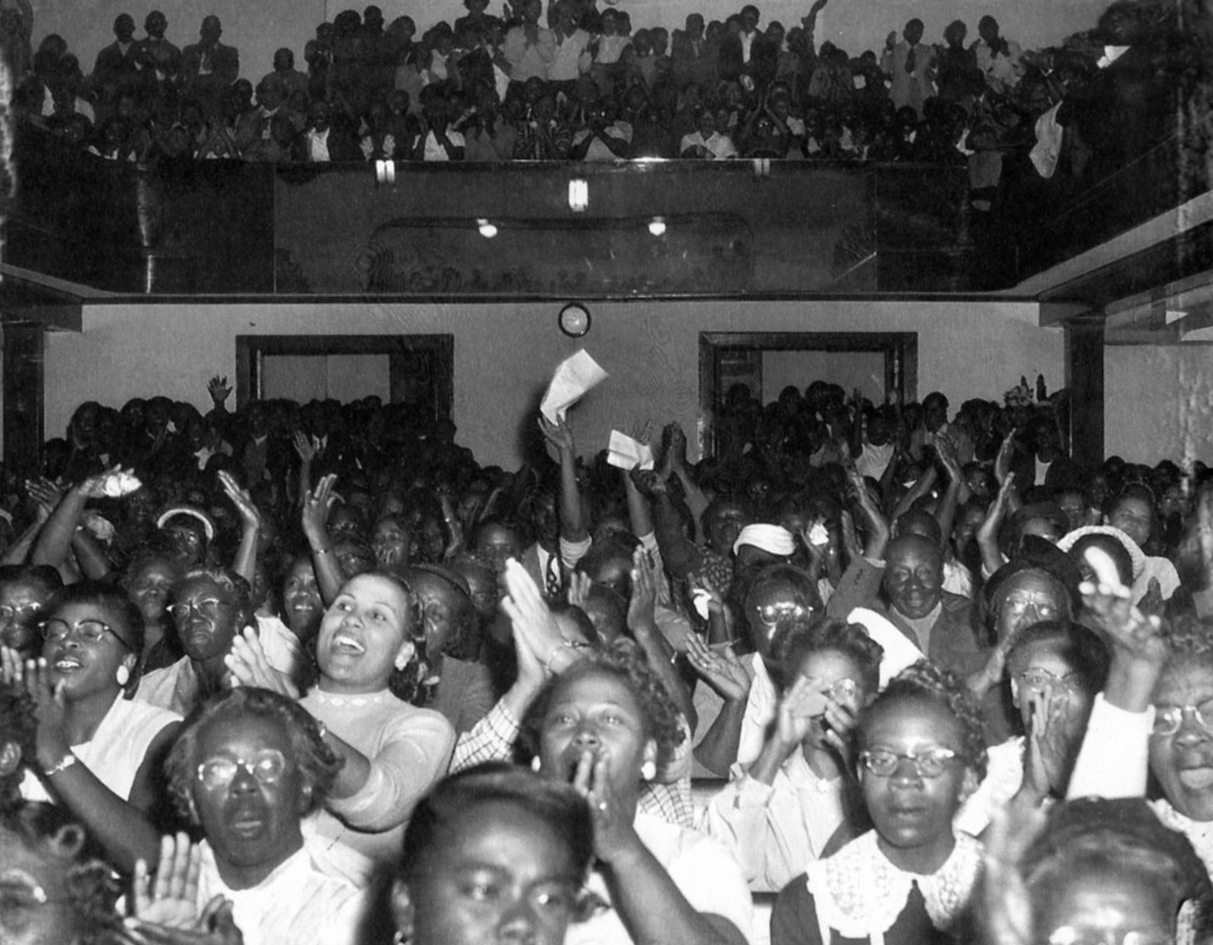

Indeed, the first official act of the Montgomery Improvement Association, an entity formed to help guide and manage the boycott, was a mass meeting at Holt Street Baptist Church led by the local preachers.

At the meeting, King gave a speech that referred to god over ten times. And he fused religion and justice in a new way, at the very start of this campaign.

And we are not wrong, we are not wrong in what we are doing. (Well) If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. (Yes sir) [applause] If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. (Yes) [applause] If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong. (That’s right) [applause] If we are wrong, Jesus of Nazareth was merely a utopian dreamer that never came down to earth. (Yes) [applause] If we are wrong, justice is a lie. (Yes) Love has no meaning. [applause] And we are determined here in Montgomery to work and fight until justice runs down like water (Yes) [applause], and righteousness like a mighty stream.

Now the underlying message of that campaign and this particular speech might not be exactly what we need today. But it was exactly what was needed then. Our task is to learn from these innovations, renew them, and implement them ourselves.

Part of the task is to renew the language of love and justice, just as the leaders of the boycott did then. This was part of innovation #4. We will continue studying and understanding all five innovations in the next several posts, god willing.

What we need today: spiritual revolution led by lovers of god

Even with this short introduction we can start to get a sense of what was different in Montgomery, and what we’re missing in movements for peace and justice today: lovers of god who involve god in the work. That is not going to be easy. Christian nationalists are trying to do the same thing, but with different goals.

Today, let us give thanks for the spiritual revolution that was born in Montgomery and spread throughout the rest of the movement, namely a good war and a good god. A good war embraces nonviolence and harmlessness. And so does a good god.

Like King, we don’t need to be involved in the genesis of the next peaceful revolution. But when it arrives, we should be ready to respond to its call.

Comments ()